A fantastic analysis that was originally posted in the Technology Review - Too often we make business decisions/assumptions based on common rhetoric without really diving into or challenging it to understand what’s really at the core (I see this quite often when reviewing business cases for improvement modifications)

This is really a nice piece of work, just to remind you to not necessarily always accept the usual assumptions as facts.

Donald Trump says that if he becomes president, he will “get Apple to start making their computers and their iPhones on our land, not in China.” Bernie Sanders has also called for Apple to manufacture some devices in the U.S. instead of China.

Neither candidate could instantly make that happen. As Steve Jobs once told President Obama when he asked why Apple didn’t make phones in its home country, the company didn’t hire manufacturers in China only because labor is cheaper there. China also offered a skilled workforce and flexible factories and parts suppliers that can, Apple believes, retool more quickly than their American counterparts.

But set that aside for now, and imagine that Apple persuaded one of its Chinese manufacturers to open factories in the United States or did that itself. Could it work? Apple could profitably produce iPhones in America, as some high-end Mac computers are produced, without making them much more expensive. There’s a catch, though, that undermines Trump’s and Sanders’s arguments. This becomes clear if you carry our thought experiment to its most extreme conclusion.

Scenario 1

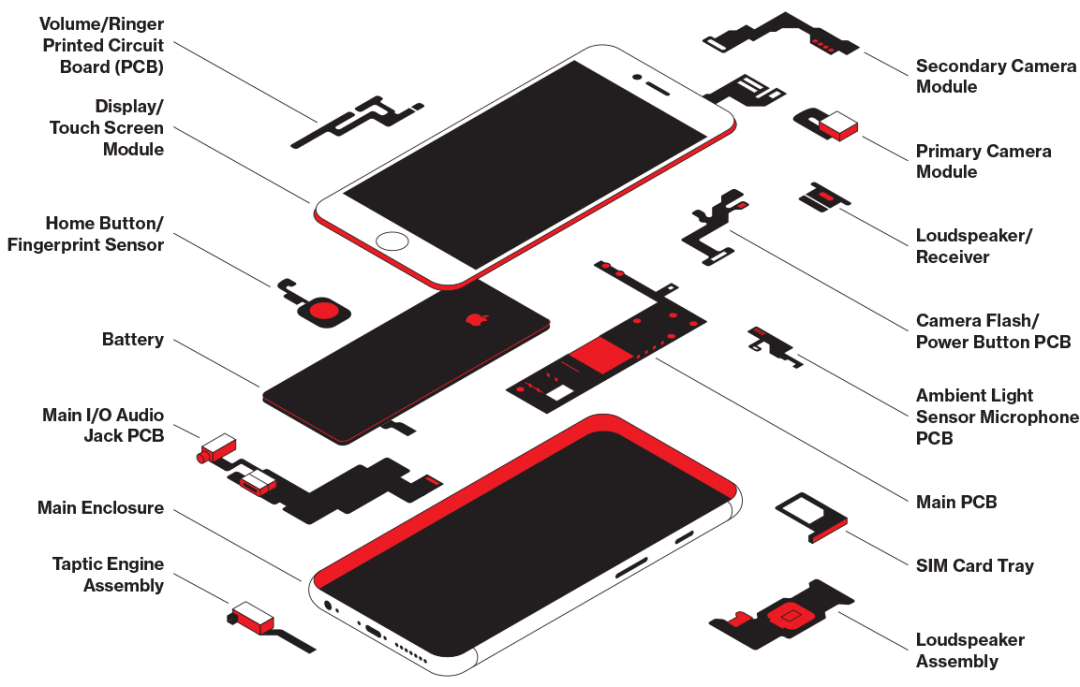

Today Apple contractors assemble iPhones in seven factories—six in China and one in Brazil. If the phones were assembled in the U.S. but Apple still sourced components globally, how much would that change the price of the device? According to IHS, a market analyst, the components of an iPhone 6s Plus, which sells for $749, cost about $230. An iPhone SE, Apple’s newest model, sells for $399, and IHS estimates it contains $156 worth of components. Assembling those components into an iPhone costs about $4 in IHS’s estimate and about $10 in the estimation of Jason Dedrick, a professor at the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University. Dedrick thinks that doing such work in the U.S. would add $30 to $40 to the cost. That’s partly because labor costs are higher in the U.S., but mostly it’s because additional transportation and logistics expenses would arise from shipping parts, and not just the finished product, to the U.S. This means that assuming all other costs stayed the same, the final price of an iPhone 6s Plus might rise by about 5 percent.

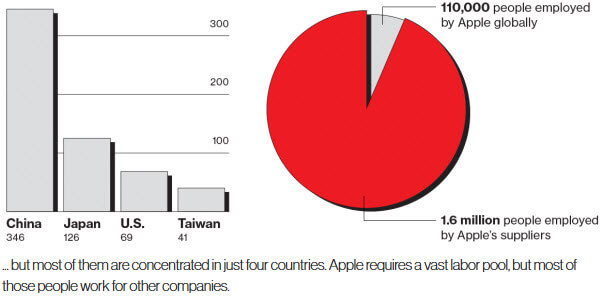

What benefits would this bring to the U.S.? Apple says its suppliers employ more than 1.6 million workers. But final assembly of the phones accounts for a small fraction of that. So even if Apple could convince Foxconn or another supplier to assemble iPhones in the U.S. without cutting into its profits too badly, that alone probably wouldn’t be as transformative as Trump and Sanders imply.

Scenario 2

What, though, if components were to be made in the U.S. as well? Almost half—346—of Apple’s 766 suppliers (counting those making parts for iPhones, iPads, and Macs) are in China. Japan has 126, the U.S. 69, and Taiwan 41. Apple has said the U.S. lacked the manufacturing infrastructure needed for the iPhone. But if it could find a way to get it done domestically, what would phones cost? The front of the iPhone is made of Corning’s tough Gorilla Glass. Corning makes the glass in facilities in Kentucky, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. The touch screen made out of that glass and computer chips underneath is one of the phone’s most expensive components. It costs about $20 in an iPhone SE, according to IHS. The other major expense is the phone’s processor. In both the SE and the 6s, this is a chip that Apple designed itself. Apple outsources the actual manufacture of the chip to Samsung and TSMC, a Taiwanese firm. The cellular modem in the SE, designed by Qualcomm, costs about $15, according to IHS. NAND and DRAM memory add another $15, power management chips $6.50, and radio amplifiers and transceivers almost another $15. Many of these chips are made under contract, so it’s hard to know exactly where they are produced. For example, GlobalFoundries, a major contract manufacturer, produces microchips for companies like Qualcomm in Germany, Singapore, New York, and Vermont. Duane Boning, an electrical engineer at MIT who specializes in semiconductor manufacturing, says he thinks there is “essentially little cost difference” from country to country in producing the wafers from which individual chips are cut. “Labor costs are a tiny fraction of cost compared to the equipment and facilities that go into a multibillion-dollar fab,” Boning says. As Alex King, director of the Critical Materials Institute headquartered at the Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, points out, semiconductor fabs become obsolete a few years after they are built. This means, he says, that “with every new generation of semiconductors there is an opportunity to place a semiconductor fab anywhere in the world, including the U.S.” The machines used in such fabs are in fact largely still made in the United States. Could this be done economically for the various chips and other components that go into an iPhone? Dedrick and his colleagues estimate that producing the constituents of an iPhone in the U.S. would add another $30 or $40 to the cost of the device. Initially, at least, “U.S. factories would be uncompetitive for most of these goods and run at low volumes, raising the differential with Asia even higher,” Dedrick points out. But it’s safe to project, he says, that in this scenario a phone would be at most $100 more expensive, assuming that the raw materials that go into the components were bought on global markets.

Scenario 3

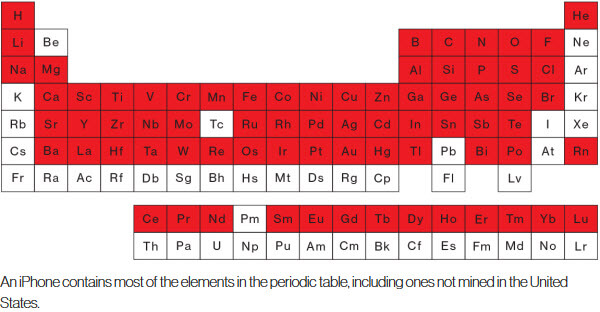

To fully grasp the importance of trade in the high-tech economy, imagine a scenario even beyond what the candidates suggest: what if Apple tried to make an iPhone out of “American atoms,” so that the U.S. would not be at all reliant on foreign governments for access to the necessary materials? According to King at the Ames Lab, an iPhone has about 75 elements in it—two-thirds of the periodic table. Even just the outside of an iPhone relies heavily on materials that aren’t commercially available in the U.S. Aluminum comes from bauxite, and there are no major bauxite mines in the U.S. (Recycled aluminum would have to be the domestic source.)

The elements known as rare earths (which aren’t that rare but are tough to mine) would need to come primarily from China, which produces 85 percent of the world’s supply. Neodymium is needed for its magnets, like the one in the motor that makes the phone vibrate and the ones in the microphones and speakers. Lanthanum, another rare earth, goes into the camera lens. Hafnium, a metal that is not a rare earth and is rarer than most of them, is essential for the iPhone’s transistors. In other words, “no tech product from mine to assembly can ever be made in one country,” says David Abraham, author of The Elements of Power, a new book about rare earth metals. The iPhone is a symbol of American ingenuity, but it’s also a testament to the inescapable realities of the global economy.