So I had a colleague ask me the other day to explain NPV in a little more detail while we were discussing investment strategies for cost reduction. I thought some others may have a similar curiosity; so have decided to run a bit of a series on interesting basic business refreshers. This first one’s on his NPV request from over at HBR.

Most people know that money you have in hand now is more valuable than money you collect later on. That’s because you can use it to make more money by running a business, or buying something now and selling it later for more, or simply putting it in the bank and earning interest. Future money is also less valuable because inflation erodes its buying power. This is called the time value of money. But how exactly do you compare the value of money now with the value of money in the future? That is where net present value comes in.

To learn more about how you can use net present value to translate an investment’s value into today’s dollars, I spoke with Joe Knight, co-author of Financial Intelligence: A Manager’s Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really Mean and co-founder and owner of www.business-literacy.com.

What is net present value?

“Net present value is the present value of the cash flows at the required rate of return of your project compared to your initial investment,” says Knight. In practical terms, it’s a method of calculating your return on investment, or ROI, for a project or expenditure. By looking at all of the money you expect to make from the investment and translating those returns into today’s dollars, you can decide whether the project is worthwhile.

What do companies typically use it for?

When a manager needs to compare projects and decide which ones to pursue, there are generally three options available: internal rate of return, payback method, and net present value. Knight says that net present value, often referred to as NPV, is the tool of choice for most financial analysts. There are two reasons for that. One, NPV considers the time value of money, translating future cash flows into today’s dollars. Two, it provides a concrete number that managers can use to easily compare an initial outlay of cash against the present value of the return.

“It’s far superior to the payback method, which is the most commonly used,” he says. The attraction of payback is that it is simple to calculate and simple to understand: when will you make back the money you put in? But it doesn’t take into account that the buying power of money today is greater than the buying power of the same amount of money in the future.

That’s what makes NPV a superior method, says Knight. And fortunately, with financial calculators and Excel spreadsheets, NPV is now nearly just as easy to calculate.

Managers also use NPV to decide whether to make large purchases, such as equipment or software. It’s also used in mergers and acquisitions (thought it’s called the discounted cash flow model in that scenario). In fact, it’s the model that Warren Buffet uses to evaluate companies. Any time a company is using today’s dollars for future returns, NPV is a solid choice.

How do you calculate it?

No one calculates NPV by hand, Knight says. There is an NPV function in Excel that makes it easy once you’ve entered your stream of costs and benefits. (Plug “NPV” into the Help function and you’ll get a quick tutorial or you can purchase the HBR Guide to Building Your Business Case + Tools, which includes an easy-to-use pre-filled spreadsheet for NPV and the other ROI methods). Many financial calculators also include an NPV function. “A geek like me, I have it on my iPhone. I like to know it’s in my pocket,” says Knight.

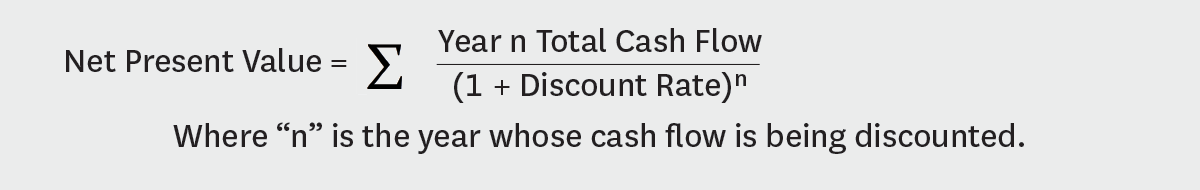

Even if you’re not a math nerd like Knight, it’s helpful to understand the math behind it. “Even seasoned analysts may not remember or understand the math but it’s quite straightforward,” he says. The calculation looks like this:

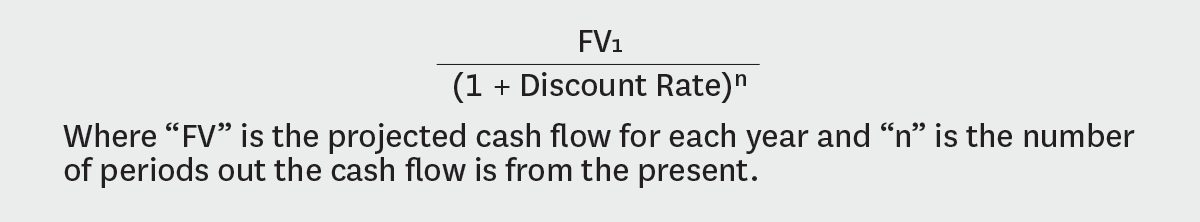

This is the sum of the present value of cash flows (positive and negative) for each year associated with the investment, discounted so that it’s expressed in today’s dollars. To do it by hand, you first figure out the present value of each year’s projected returns by taking the projected cash flow for each year and dividing it by (1 + discount rate). That looks like this:

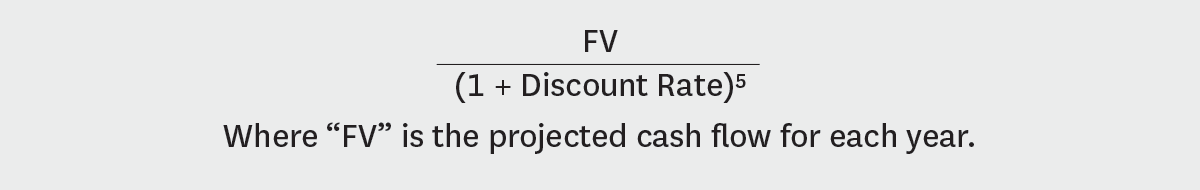

So for a cash flow five years out the equation looks like this:

If the project has returns for five years, you calculate this figure for each of those five years. Then add them together. That will be the present value of all your projected returns. You then subtract your initial investment from that number to get the NPV.

If the NPV is negative, the project is not a good one. It will ultimately drain cash from the business. However, if it’s positive, the project should be accepted. The larger the positive number, the greater the benefit to the company.

Now, you might be wondering about the discount rate. The discount rate will be company-specific as it’s related to how the company gets its funds. It’s the rate of return that the investors expect or the cost of borrowing money. If shareholders expect a 12% return, that is the discount rate the company will use to calculate NPV. If the firm pays 4% interest on its debt, then it may use that figure as the discount rate. Typically the CFO’s office sets the rate.

What are some common mistakes that people make?

There are two things that managers need to be aware of when using NPV. The first is that it can be hard to explain to others. As Knight writes in his book, Financial Intelligence, “the discounted value of future cash flows — not a phrase that trips easily off the nonfinancial tongue”. Still, he says, it’s worth the extra effort to explain and present NPV because of its superiority as a method. He writes, “any investment that passes the net present value test will increase shareholder value, and any investment that fails would (if carried out anyway), actually hurt the company and its shareholders.”

The second thing managers need to keep in mind is that the calculation is based on several assumptions and estimates, which means there’s lots of room for error. You can mitigate the risks by double-checking your estimates and doing sensitivity analysis after you’ve done your initial calculation.

There are three places where you can make misestimates that will drastically affect the end results of your calculation. First, is the initial investment. Do you know what the project or expenditure is going to cost? If you’re buying a piece of equipment that has a clear price tag, there’s no risk. But if you’re upgrading your IT system and are making estimates about employee time and resources, the timeline of the project, and how much you’re going to pay outside vendors, the numbers can have great variance.

Second, there are risks related to the discount rate. You are using today’s rate and applying it to future returns so there’s a chance that say, in Year Three of the project, the interest rates will spike and the cost of your funds will go up. This would mean your returns for that year will be less valuable than you initially thought.

Third, and this is where Knight says people often make mistakes in estimating, you need to be relatively certain about the projected returns of your project. “Those projections tend to be optimistic because people want to do the project or they want to buy the equipment,” he says.